Scales presented in an easy way

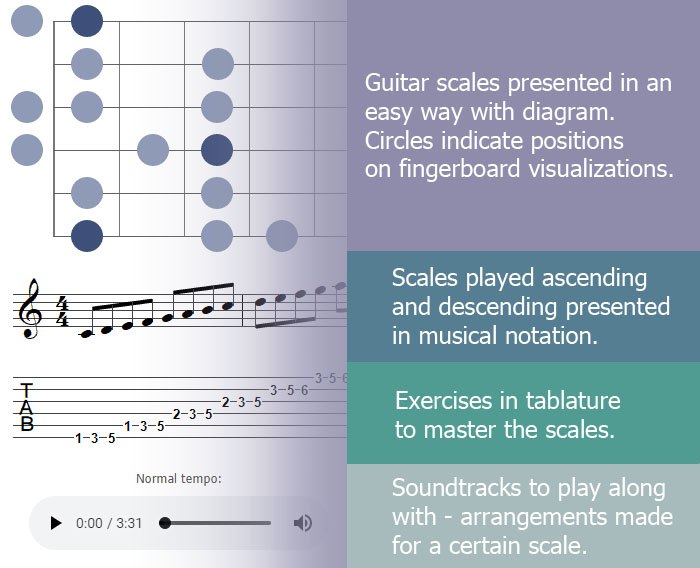

This site has set a goal to present scales in a way all players including beginners can understand. To enhance the learning, scales are presented with various diagram styles:

- Based on octaves (from the root note to the same note on a higher octave).

- Based on shapes (which can be interconnected on the guitar neck).

- Full fretboard diagram (i.e., 15 frets which is sufficient to cover the vital part of the fretboard).

- Diagrams including note names.

The goal is also to deliver additional information so that ambitious musicians can study scales and understand them on a deeper level. By clicking on the collapsible panels on the scales’ presentation pages, more information is available including scale degrees, related chords and theoretical explanation.

What is a scale?

A scale in music is constructed from a series of tones. The number of tones varies, Major and Minor scales, for example, contains seven tones of twelve possible semi-tones. Such series of tones will sound great played together and are often used as foundation for composing or improvisation. In scale, tones are arranged in a specific order, but they can be played in any order – playing them from root to root is only when practicing.

A distinction can be made between rhythm and lead guitar. In a rock band with two guitarists, one could play the rhythmic parts whereas the other guitarist plays the solo parts. A guitar solo is often based upon one or several scales. In blues and jazz, improvisation is a very common element and improvisations are often played “over” chords. This means that the improvised melody is based on scales that match the chords. Thus, a musical improvisation is in realty seldom a completely free improvisation since it is grounded from a framework.

Why should you learn them?

So, why bother at all with these collections of tones that has a lot of strange names? There is actually a great idea to invest time with scales and here are some of the reasons:

- You will develop your technique and finger flexibility. Playing through scale patterns involves repeating different fingerings and shifting of hand positions.

- You will train your ear. Playing through major and minor scales, for example, will develop your ability to hear if a song is in major or minor, which is a powerful skill for a musician.

- You can easier learn songs because you get an understanding for keys and by knowing which key a song is played in, you will be able to learn it faster. If you know the tones of a key, you will also know all the tones that can be used in a song and by that you no longer starting from scratch when memorizing a new song. Instead, you can exclude all notes that you know don’t “fit in”.

- You get important tools for composing music, since you know which notes that “fits together” in general.

- You will establish devices for creating solos. Scales work as a framework, or as a palette, for notes that you can use when you improvise to the music from other instruments. Understanding the concepts of scales are crucial for learning how to play along with other musicians if you are a lead guitarist.

These are some of the reasons that makes scales the most fundamental knowledge alongside chords for guitarists.

How to play a scale?

First of all when you learn a new scale, it is recommended to play it from start to end and back a couple of times, just to get it under your fingers. The animated diagram below shows how the scale in A major can be played ascending and descending over one octave. This is just one of many patterns for that specific scale, but it is a good starting point for training.

When you practice on scales, it is important to use adequate fingerings. If three notes are included on one string, you should use three fingers and to avoid moving your hand to much you should also include the little finger when it makes the run over the fretboard more efficient. See further guidelines for fingerings below.

While the piano lines up linear, the guitar is parallel. That means that the order of tones continues from string to string. From the bass tones on first frets of the lowest string (equivalent of the left side of the piano keyboard) via the middle strings to the last fret on the highest string (equivalent of the right side of the piano keyboard).

Fingering patterns

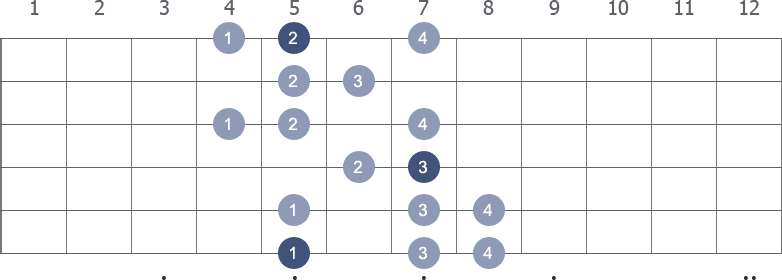

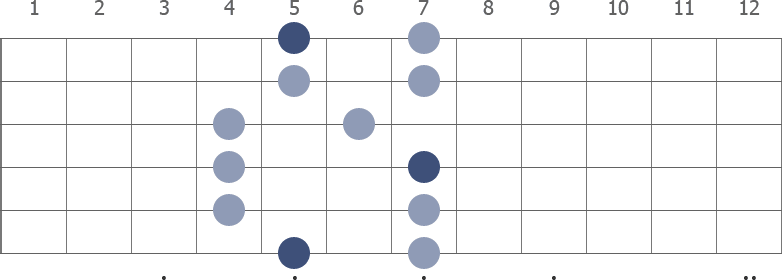

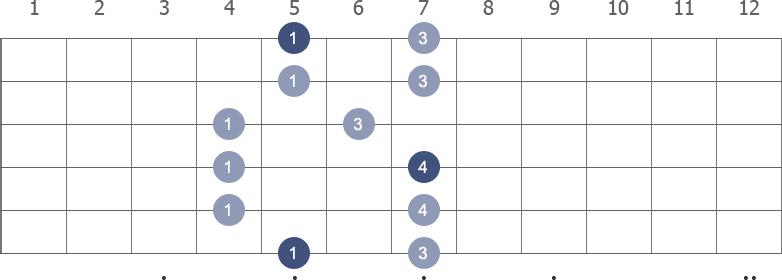

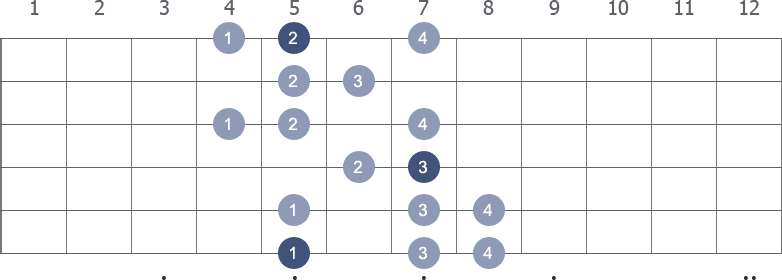

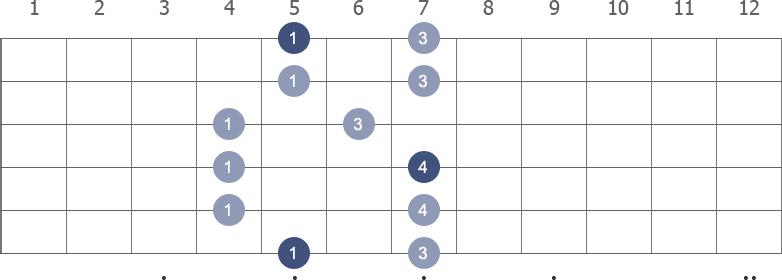

Some patterns are favorized and tends to be used more than others, but there is often more than one proper fingering for a scale. Often, the choice is between avoiding stretches or hand transitions. Compare the following two diagrams, which contain the same notes but with different fingerings:

Above: This finger pattern of the A Minor Harmonic scale uses a pattern that avoids big stretches, but include position shifts.

Above: This finger pattern of the A Minor Harmonic scale uses a pattern that accepts big stretches, but stays at the same position. Enables faster playing and often favored by guitarists with big hands.

*

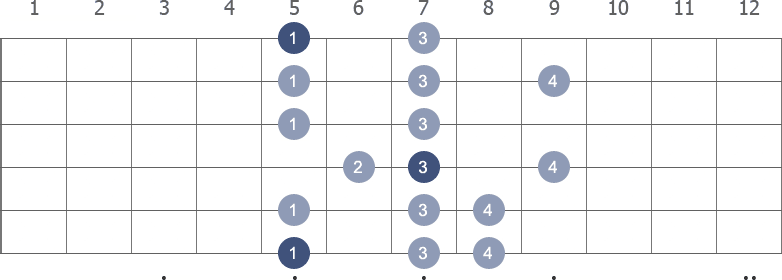

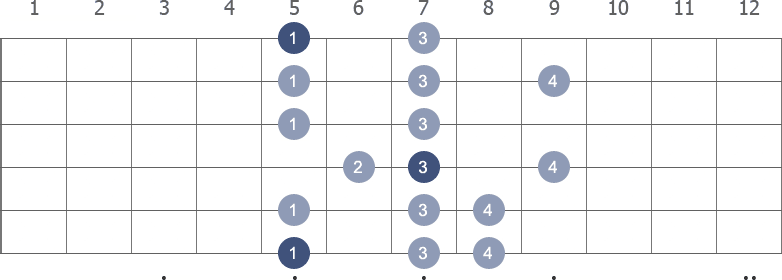

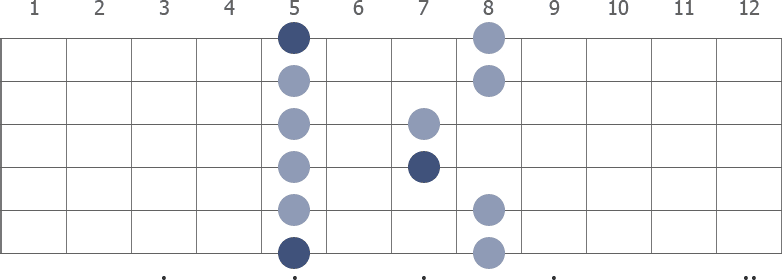

Proper fingering will make smoother playing and by the same time strengthen the fingers – although it could be harder in the beginning, it will benefit your development in the long run. Consider the diverse approaches in the next two diagrams for the same scale:

Above: This finger pattern of the A Pentatonic Major scale uses a pattern that include all fingers and avoid position shifts.

Above: This finger pattern of the A Pentatonic Major scale uses a pattern that chose the stronger fingers, but include position shifts with the index finger moving between the fifth and fourth frets. This approach to scale fingering is not recommended.

Octaves versus boxes

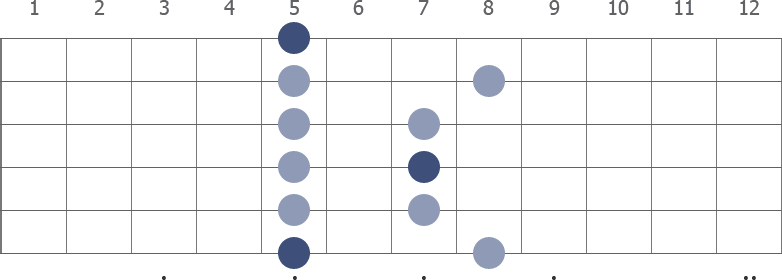

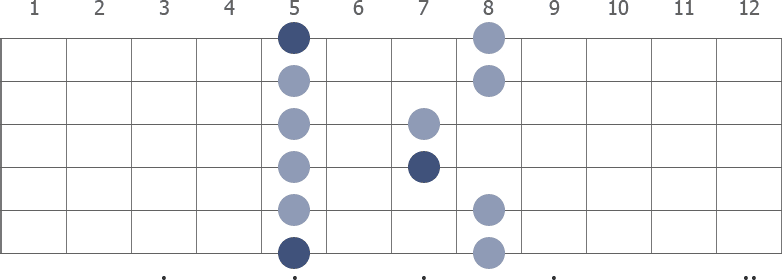

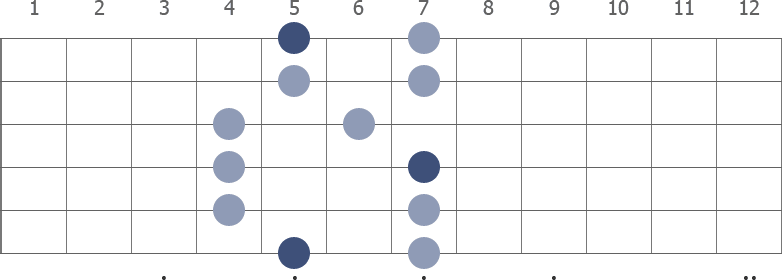

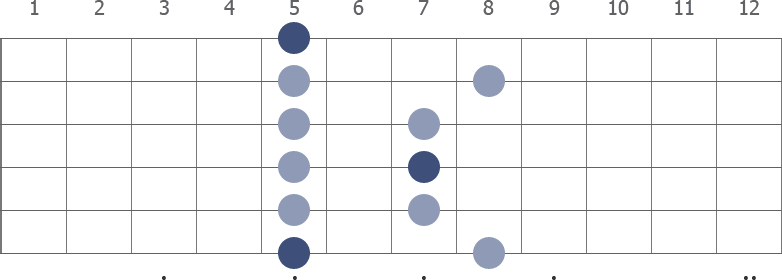

Scales can be learned and employed in many ways, but mainly based on octaves or boxes. For an instrument such as the piano, the octave approach is by far the most natural whereas there are room for alternatives when it comes to the guitar. Compare the following two diagrams, which contain the same scale but presented slightly different:

Above: This notes of the A Pentatonic Minor scale presented as two octaves, which starts and ends on the tonic and soundwise makes a lot of sense when playing ascending-descending.

Above: This notes of the A Pentatonic Minor scale presented as a box in the fifth position, which include all the relevant notes in the given position and is helpful to visualize in the attempt to learn the scale over the whole fingerboard, which is done by the merging of boxes in several positions.

None of the presentations are incorrect and each has its advantages. Guitarscale.org provide, in many cases, graphic displays of both alternatives.

Learn and memorize scales

The first step is to study diagrams, such presented on this site, and practice them (perhaps in conjunction with tabs or notes). Scales are often learned in parts of one or two octaves. The final goal, however, is to be able to play the scale over the whole fingerboard. The latter will be possible after the guitarist has been familiar with the scale and learnt it in different positions.

The hard part is to memorize scales. Being able to visualize different scales all over the fretboard is not achieved in a short time. A tip is to take a shortcut by learning the intervals. Here are the intervals for the Dorian scale: 2 - 1 - 2 - 2 - 2 - 1 - 2. This means that whenever you start on a root note, you can go two steps up or down the fretboard on the same string. After that you can go another one step up or down. And after that, go can go two steps up or down three times in a row — still all on the same string. When, you can go one step in either direction and finally two steps in either direction to return to the root note. By this method you can move all over the fretboard with speed just minutes after you know the intervals of the scale! You should also notice that scales, in general, are movable. Meaning that the same shape of notes can be moved up and down on the fingerboard. The C major will become C# major and fret up and so on.

Modes

In relationship to scales, modes can be seen as modifications of a scale. Modes use the same notes, but the order is reorganized. Despite the fact that exactly the same notes are involved, the modes sound different. Why? This is because of the alternative order of the intervals. Although they partly overlap, the overall interval pattern changes and that results in a different character of sound. The most common modes in music are Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian and Locrian. These goes back to the Ancient Greece and are still used in music today (dependent of the music genre, some of them will be more relevant than others when it comes to lead guitar playing).

See also

Scale exercises Jam tracks Arpeggios

* * *

If you have any concern or have suggestions concerning the subject treated on this site, feel welcome to contact us by mail, contact@guitarscale.org.